Definition and Function of Electrical Fuses

An electrical fuse is a safety device designed to protect circuits against excessive current. It typically consists of a filament or metallic strip with a low melting point, placed in series within the installation. When the current exceeds a safe threshold—due to a short circuit or an overload—the filament heats up due to the Joule effect and melts, breaking the circuit. In this way, the main function of the fuse is to interrupt the electrical flow before the overcurrent causes serious damage, preventing fires, equipment failure, and electric shock hazards to people.

What Is a Fuse in Electricity?

In electricity, a fuse is essentially a “controlled weak point” within an electrical circuit. It consists of a body (glass, ceramic, or another insulating material) that houses a calibrated metal conductor inside. This conductor is usually a metallic alloy (e.g., lead-tin, copper, or silver) that melts at a specific temperature. The fuse is installed in series so that all the circuit current passes through it. Under normal conditions, the fuse allows the current to flow without issue. However, if the current exceeds the fuse’s rated value for a sufficient period, the heat generated melts the filament and breaks it.

At that moment, the circuit is open (interrupted) and the current stops flowing. This simple yet effective mechanism stops any dangerous overcurrent situation before downstream conductors or equipment suffer damage. In short, a fuse in electricity is a sacrificial component designed to fail (melt) in a controlled way to save the rest of the installation.

What Is a Fuse Used For and Why Is It Important?

The fuse ensures the safety and integrity of an electrical installation, protecting both people and equipment. Its importance lies in the fact that it acts as a guardian against electrical anomalies that, if left unchecked, could have serious consequences. Some key reasons why a fuse is so important include:

- Protection of devices and wiring: Prevents an overcurrent from damaging appliances, machines, or costly electronic components. By blowing in time, the fuse stops current from reaching levels that could harm internal circuitry.

- Fire prevention: Excessive current can overheat conductors (wires), burning insulation or surrounding materials. The fuse, by cutting the current before this occurs, significantly reduces the risk of fire caused by electrical faults.

- Prevention of cascading failures: In an electrical installation, a short circuit in one section could damage the entire network if not stopped quickly. The fuse isolates the fault and sacrifices itself, preventing the anomaly from spreading to other connected devices or circuits.

- Personal safety: Indirectly, by preventing fires and disconnecting faulty circuits, fuses protect individuals from dangerous situations such as electric shocks or house fires. Many electrical codes and regulations require their use to safeguard human life.

Despite their low cost and simplicity, fuses remain one of the most reliable protection methods. In any environment—residential, commercial, industrial, or automotive—they are essential for safe operation, providing assurance that any abnormal condition will immediately trigger current interruption.

Types of Electrical Fuses

There are several types of electrical fuses, each designed for specific applications and conditions. When choosing the right fuse, it is important to consider the rated current, response time, and operating environment. Below are the most common types:

- Cartridge fuses: These are the most common in residential and industrial installations. They have a cylindrical shape (sometimes with metal terminals at the ends) and are housed in fuse holders or dedicated bases. The fuse element is usually enclosed in a ceramic or glass tube. They provide reliable protection against both prolonged overloads and current spikes caused by short circuits. Commonly used in traditional electrical panels and line protection.

- Ultra-fast or thermal fuses: Also known as fast-acting fuses, they are designed to respond almost instantaneously to overcurrents. They are ideal for protecting sensitive electronic equipment (e.g., power supplies, lab instruments, frequency inverters, etc.) where even a short overvoltage could cause damage. Their construction allows them to blow in extremely short times, limiting the energy transferred during a fault. This category includes semiconductor fuses and “quick blow” types widely used in electronics.

- Resettable fuses (polyfuses): Unlike traditional single-use fuses, polyfuses (PTC polymer fuses) are not permanently destroyed. When the current exceeds a certain threshold, the internal polymer material drastically increases its resistance, effectively stopping the current. Once the fault is removed and the component cools down, the fuse “resets” and returns to its normal conductive state. They are used in electronic devices and circuits where permanent loss of protection is not desirable (e.g., on printed circuit boards, chargers, USB ports, etc.). However, they have limited current-handling capacity and are generally used to protect against moderate overcurrents or minor short circuits in electronics.

- High-capacity fuses: These fuses are designed for high currents and power levels, typical in industrial and electrical distribution settings. They include large blade-type or NH (German standard) fuses used in main low-voltage panels, motor control centers, and heavy machinery. They have very high breaking capacities (capable of interrupting short-circuit currents of tens of kiloamperes) and are mounted in robust fuse bases. These fuses protect main power feeds, transformers, high-power motors, and other critical industrial loads.

Choosing the right type of fuse will depend on the characteristics of the installation: the rated current level, the sensitivity of the loads to be protected, and the expected short-circuit current. In practice, for a household installation, standard cartridge fuses (or nowadays automatic breakers) are typically used, while an ultra-fast fuse would be selected for delicate electronic systems, and a high-capacity fuse—such as type aM—for industrial motors.

Comparison Table of Fuse Types

The following table summarizes and compares the different types of fuses mentioned, highlighting their main features and typical applications:

| Fuse Type | Main Features | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cylindrical cartridge | Internal filament housed in a glass or ceramic tube. Good breaking capacity and standard response time. | Residential and industrial panels, general line protection, household appliances. |

| Ultra-fast (quick-acting) | Fuse element designed to melt in milliseconds under surges. Minimizes fault energy. | Sensitive electronic equipment, power supplies, measuring devices, power semiconductor circuits. |

| Time-delay (slow-blow) | Withstands brief overloads (e.g., motor startup) without melting. Delayed response to moderate overcurrents. | Protection of electric motors, transformers, or loads with inrush currents; devices requiring tolerance for momentary surges. |

| Resettable (PTC) | Polymer material increases resistance with high current. Resets automatically upon cooling, no replacement needed. | Electronic circuits, PC ports and peripherals, chargers, devices where automatic reset is preferred. |

| High-capacity (NH, blade) | Large fuses with high amperage ratings (tens to hundreds of amps) and high breaking capacity (up to tens of kA). | Industrial installations, main low-voltage panels, distribution systems, protection of main feeders, battery banks, etc. |

Note: In addition to those listed above, there are special fuses for specific applications, such as automotive blade-type fuses used in vehicles, or thermal fuses (temperature-sensitive) for overheating protection. However, those listed in the table are the most common for overcurrent protection.

Practical Examples of Use in Different Sectors

Fuses are used across a wide range of sectors. Here are some practical examples of their application in different contexts:

- Residential sector: In homes and buildings, fuses (or today, their automatic counterparts) protect lighting circuits, power outlets, and appliances. Although modern domestic installations typically use miniature circuit breakers, many homes still have cartridge fuses in older distribution boxes or within individual devices (e.g., some power strips, plug adapters, or air conditioners include internal fuses).

- Industrial sector: In factories and industrial buildings, high-capacity fuses are used in switchboards to protect distribution lines and heavy machinery. They also safeguard electric motors, capacitor banks, variable frequency drives, and control systems. For example, in motor control centers (MCCs), NH-type fuses are commonly used to protect each power circuit. Their reliability and fast operation make them ideal safety backups in demanding industrial environments.

- Automotive: Cars, trucks, and other vehicles have fuse boxes protecting all electrical systems. Each circuit (lights, wipers, horn, audio system, fans, etc.) is connected through a fuse with a specific amperage. If a component short circuits or draws excessive current, the corresponding fuse will blow, preventing further damage and helping identify the fault. Automotive fuses are usually flat-blade types with color coding to indicate amperage.

- Electronics and telecommunications: In precision electronics (medical instruments, lab equipment, computers, telecom systems), fast-acting low-value fuses (in milliamps or a few amps) protect sensitive components. For instance, a power supply in a TV or computer will include small glass fuses; a router may have polyfuses at its input ports to prevent minor overvoltage damage. These fuses ensure that internal failures are contained and do not cause fire.

- Renewable energy: In photovoltaic solar installations, fuses are commonly used on each string (panel series) to protect against reverse currents or faults between panels. These are DC fuses specifically rated for string voltages (e.g., 1000 VDC) and are typically installed in fuse holders inside solar combiner boxes. Likewise, wind turbines and battery storage systems use high-capacity fuses to isolate faults in renewable energy systems.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What happens when a fuse blows? – When a fuse burns out, the circuit is opened and current stops flowing. It is necessary to identify the cause of the overcurrent and, after resolving it, replace the blown fuse with a new one of the same type and amperage to restore service.

- What’s the difference between a fast-blow and a slow-blow fuse? – A fast-blow fuse (quick-blow) reacts almost instantly to any overcurrent, even brief surges, making it ideal for protecting sensitive devices. A slow-blow fuse (time-delay) can tolerate short-duration overcurrents (such as motor startups) without blowing but will melt if the overcurrent persists. The difference lies in the time-current curve of each type.

- How do I know which type of fuse I need? – You need to know your circuit or device’s rated current and load type. Then select a fuse with an amperage slightly above the expected operating current. If the load includes brief surges (motors, transformers), a slow-blow fuse may be suitable; if it’s sensitive electronics, opt for a fast-blow. Always consult the manufacturer’s specifications or electrical codes for guidance.

- Is it mandatory to install fuses? – Yes, electrical regulations (such as the Low Voltage Electrotechnical Regulations in Spain) require overcurrent protection devices in almost all circuits. These can be fuses or equivalent automatic circuit breakers. While miniature circuit breakers are common, if they are not present, fuses must be installed. In certain locations (such as the main entry point to a home or internal device protection), fuses are often the most practical and compliant solution.

- Can I replace a fuse with one of higher amperage so it doesn't blow? – No. Installing a fuse with a higher amperage than specified eliminates the circuit’s effective protection. In case of a moderate overcurrent, the new fuse may not blow in time—if at all—leading to potential damage. Always replace fuses with the same nominal rating and characteristics. If a fuse blows frequently, it indicates a problem in the circuit or an incorrect fuse value—not something to fix by "increasing amperage" without proper technical assessment.

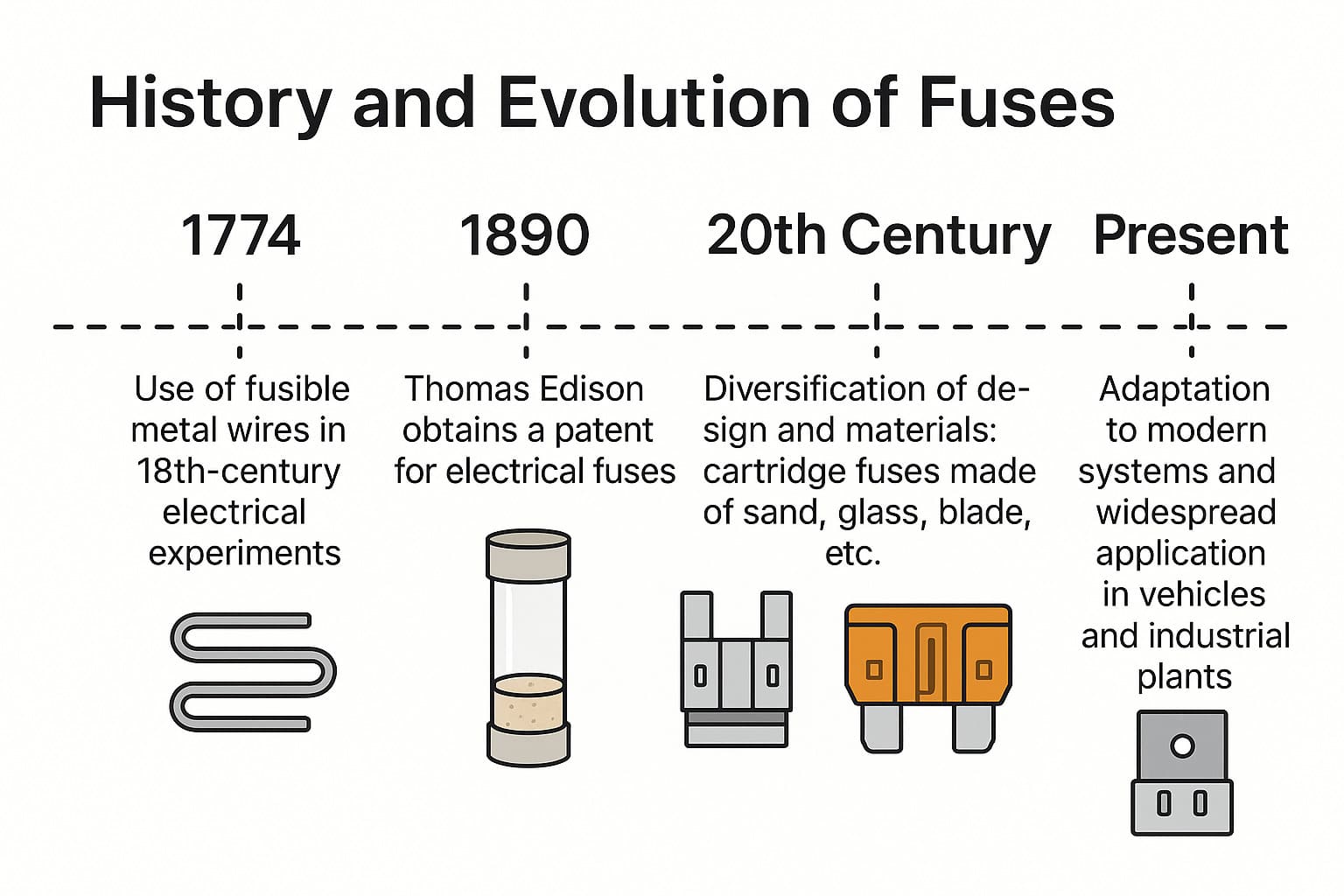

History and Evolution of Fuses

The electrical fuse is one of the oldest and most essential protective devices in the history of electrical engineering. Its origins date back to the 18th century, when in 1774 metal fuse wires were used in scientific experiments to prevent damage to early capacitors and rudimentary devices. These wires acted as primitive safety measures, breaking when exposed to excessive electrical discharge.

However, it was not until the late 19th century, with the expansion of global electrification, that the fuse became a fundamental component in power distribution systems. In 1890, the famous inventor Thomas Alva Edison obtained one of the first patents related to electrical fuses, promoting their use in the DC distribution networks of the time. This advancement was key to improving safety in urban installations spreading across cities like New York and London.

Throughout the 20th century, with the widespread adoption of alternating current and growing demand for electricity in both industry and homes, fuses evolved in design and materials. Cartridge fuses with sand filling were developed to efficiently extinguish the electric arc after activation, increasing their breaking capacity. Glass fuses emerged for small electronic devices, along with blade-type (NH) fuses essential in industrial installations and high-power systems.

The appearance of specialized variants allowed fuses to adapt to new technological demands: ultra-fast fuses for protecting sensitive electronic devices, time-delay fuses designed to handle motor startup currents, and automotive fuses (such as modern colored flat mini-fuses) widely used in vehicles. Today, a car may include between 30 and 60 fuses in various boxes, protecting the advanced electronics that control everything from lighting to engine management and safety systems.

Despite the rise of more sophisticated solutions like miniature circuit breakers and residual current devices (RCDs), the fuse remains irreplaceable in many contexts. Its simplicity, reliability, and low cost make it the first line of defense against overloads and short circuits. Today, fuses are manufactured with ratings ranging from just a few milliamps for protecting electronic circuits to models capable of withstanding and disconnecting short-circuit currents over 100 kA, as used in large industrial installations and high-voltage electrical networks.

Tens of millions of fuses are produced worldwide every year, reflecting their essential role in ensuring the safety of both residential and industrial installations. From small appliances to complex photovoltaic solar energy systems, fuses continue to protect critical equipment and safeguard lives.

In short, the history of the fuse is a clear example of how a seemingly simple device can evolve to meet the most demanding technological needs, remaining a cornerstone of modern electrical safety. Its effectiveness and rapid response to faults continue to save equipment—and lives—around the world, making it an indispensable component in any professional electrical installation.

Technical Comparison with Miniature Circuit Breakers (MCBs) and Residual Current Devices (RCDs)

In modern electrical protection, fuses coexist with other devices such as miniature circuit breakers (MCBs) and residual current devices (RCDs). Each has a specific role and different technical characteristics. Below is a comparison of their functions and key differences:

| Characteristic | Fuse | Miniature Circuit Breaker (MCB) |

|---|---|---|

| Operating mechanism | Melts and destroys. Single-use only. | Internal mechanism that can be reset manually. |

| Protection against | Overloads and short circuits. | Overloads (thermal) and short circuits (magnetic). |

| Reaction time | Very fast, excellent current-limiting in short circuits. | Fast, especially in short circuits, though typically slower than fuses. |

| Breaking capacity | Up to 50 kA or more (industrial fuses). | Up to 6 kA or 10 kA in standard residential models. |

| Reusability | No, must be replaced after tripping. | Yes, can be reset after clearing the fault. |

| Ease of use | Low: requires physical replacement. | High: resettable, with visual trip indicator. |

| Cost | Low, but requires ongoing replacements. | Higher initial investment, lower long-term cost. |

| Common applications | Industrial installations, sensitive electronic equipment. | Residential, commercial, and industrial installations. |

- Fuse vs. MCB: Both protect against overcurrent (overloads and short circuits), but operate differently. The fuse melts and “sacrifices” itself when the current exceeds the limit, making it a one-time-use device. An MCB, on the other hand, is a reusable device that trips an internal switch mechanism when detecting overcurrent, which can then be reset manually. A well-sized fuse responds extremely fast, especially under extreme short circuits, effectively limiting fault energy. MCBs also respond quickly (their magnetic component trips almost instantly under a significant short circuit), but typically have a lower breaking capacity—residential units are rated for 6 kA or 10 kA, while industrial fuses may exceed 50 kA. MCBs are more convenient, combining overload (thermal) and short-circuit (magnetic) protection with a switch handle for easy reset and status indication.

- Fuse vs. RCD: These devices have different, complementary functions. An RCD does not protect against overcurrent but against earth leakage currents (ground faults), which could mean someone is receiving an electric shock or there is a dangerous insulation fault. If the current leaving the phase does not match the return current in the neutral (typically differing by more than 30 mA in residential environments), the RCD disconnects the circuit to prevent electrocution or damage. A fuse does not detect this type of fault, as it only reacts to absolute current values—not imbalances. Therefore, it is common to use fuses or MCBs to protect against overcurrent, and RCDs to protect people against electric shock. In modern panels, both are installed: MCBs (or fuses) per circuit for overload/short-circuit protection, and RCDs to protect groups of circuits from ground faults. It's crucial not to substitute one for the other—they are not interchangeable but work together to ensure full protection.

In conclusion: fuses offer simplicity, high-speed operation, and superior fault current interruption, making them ideal for backup protection or critical reliability points. MCBs provide resettable functionality and combined protections, practical for distribution boards. RCDs add vital protection against electrical shock. Rather than being alternatives, these devices are best used together in a well-designed installation to ensure comprehensive electrical safety.

Technical Considerations: Time-Current Curves, Materials, IEC Standards

Time-current curves: Each fuse has a specific response profile, known as its time-current characteristic. This curve indicates how long the fuse takes to blow at different levels of overcurrent. For example, a fast-acting fuse may blow in fractions of a second at a moderate overcurrent, whereas a slow-blow fuse may endure a mild overload for several seconds or even minutes. Generally, the higher the overcurrent, the faster the fuse melts. Manufacturers provide charts or tables of these curves to help engineers choose the right fuse for each application. It's essential to select a fuse with a curve that ensures both protection and durability—for instance, a motor’s startup may draw 5–7 times its nominal current briefly; a fast-acting fuse might blow unnecessarily, so a time-delay fuse (e.g., class aM) would be more appropriate.

Materials: The materials used in fuses greatly affect their performance. The fusible element (internal wire or strip) is made of an alloy with a calibrated melting point, such as lead-tin, silver, zinc, or copper alloys. In high-capacity fuses, pure silver or copper-tin alloys are common due to their excellent conductivity and clean melting behavior. Many power fuses are filled with special silica sand inside the cartridge to quench the electric arc upon melting, absorbing energy and enhancing breaking capacity. The body may be glass (for visibility in small fuses) or ceramic in higher-power versions, as ceramic withstands extreme heat and pressure. Terminals are often nickel-plated brass or other corrosion-resistant conductive metals. Modern fuses may also include indicators or mechanical triggers to show when they've blown—some industrial fuses have a viewing window or ejecting pin for easy identification.

IEC Standards and classification: Fuses are internationally standardized for safety and compatibility. IEC 60269 (and equivalents such as EN/UNE) defines the most used low-voltage fuse classes, such as gG (general-purpose), aM (motor protection, short-circuit only), ultra-fast fuses for semiconductors, etc. These standards specify dimensions, time-current curves, breaking capacity, testing, markings, and color codes to ensure that fuses from different manufacturers are interchangeable if compliant. In addition to IEC 60269 for power fuses, IEC 60127 covers miniature fuses for electronics, and ISO/SAE standards apply to automotive fuses. National electrical codes often mandate fuse use—e.g., Spain’s Low Voltage Electrical Regulation requires overcurrent protection on all circuits using CE-marked devices. Always check that a fuse bears the proper certifications (e.g., CE, IEC/EN) before installation to ensure safety and compliance.

Installation and Maintenance Tips

To ensure fuses function correctly and safely, it's essential to follow good practices during both initial installation and maintenance or replacement. Here are some important recommendations:

- Disconnect the power: Always switch off the circuit's power before handling a fuse. This prevents electric shock and arc flash hazards, especially in high-power systems.

- Check the rating and type: When replacing a blown fuse, always use one with the same amperage, type, and speed rating. Never substitute fast-blow fuses for slow-blow ones or vice versa unless you're technically qualified to do so. The new fuse must have at least the same breaking capacity as the original to ensure safe operation.

- Proper installation in its holder: Insert the fuse firmly into its base or fuse holder. A loose contact can cause terminal overheating, false tripping, or even damage. For screw-in fuses (e.g., DIAZED type), ensure they’re tightened properly with the correct adapter. Clean any oxidized or corroded terminals before installing the fuse to guarantee good electrical contact.

- Never bypass a fuse: You should never override a fuse by “bridging” it (placing a wire in its place) or using makeshift materials like aluminum foil to restore current flow. This disables protection and poses a severe fire and shock hazard. If a fuse keeps blowing, the root cause (e.g., short circuit or overload) must be investigated, not bypassed.

- Location and identification: It's useful to label fuse holders in the electrical panel to indicate which circuit they protect. This allows for quick identification when a fuse blows. Keeping organized and accessible schematics helps locate and understand each fuse’s function.

- Keep proper replacements on hand: In critical environments, it's a good idea to stock spare fuses of the right type and rating. This minimizes downtime if a fuse blows. For example, a factory panel should have spares for each fuse size used in machinery, or a home might have assorted fuses ready to replace those in older panels.

- Preventive maintenance: Although fuses don't require active maintenance (they remain dormant until needed), it’s recommended to periodically inspect fuse holders: check for signs of overheating (discoloration, burnt smell), ensure connection screws are tightened, and verify fuses are seated correctly. In dusty or humid environments, ensure contacts are clean and corrosion-free.

By following these guidelines, fuses will offer reliable and long-lasting protection. A properly chosen and installed fuse can remain in place for years, quietly doing its job—until the day it saves the system by responding to a fault.

Real-World Examples of Failures Due to Improper Fuse Selection or Absence

To understand the importance of correctly selecting and installing fuses, consider the following examples of what can go wrong when this is overlooked:

- Case 1 – Bypassed fuse causes fire: In an old home, a lighting circuit fuse frequently blew. Instead of investigating the cause (which turned out to be an intermittent short in a lamp), someone "bridged" the fuse with a thick copper wire. Days later, a major short circuit occurred: with no fuse protection, the fault current kept flowing until wires caught fire. The resulting blaze in the panel spread to nearby furniture. Fortunately, there were no injuries, but material damage was severe. This incident shows why fuses must never be bypassed—it’s better to deal with a nuisance trip than risk a fire.

- Case 2 – Overload damages equipment due to oversized fuse: In an industrial workshop, a 5 kW electric motor was protected by 32 A fuses—too high for its nominal current (around 22 A). During a mechanical jam, the motor drew excessive current. The 32 A time-delay fuses reacted too slowly due to their high rating, and the motor windings overheated and burned before the fuses operated. The motor was ruined. Proper 25 A gG fuses or a thermal relay might have disconnected the circuit in time. This case highlights that overrating a fuse "just in case" can leave equipment unprotected.

- Case 3 – Incorrect replacement in a vehicle: A car owner noticed the cigarette lighter fuse kept blowing (also powering a charger). Instead of identifying the cause (a faulty accessory causing a short circuit), they replaced the 15 A fuse with a 30 A one. Days later, the wiring overheated due to the excessive current, melting insulation and causing a near-fire under the dashboard. Luckily, smoke alerted the driver in time. This example underscores that fuses should never be replaced with higher-amperage ones than those specified, especially in vehicles where fire risks in tight spaces are critical.

Each of these real-life cases teaches the same lesson: fuses must be properly selected and installed, and should never be bypassed or replaced with inappropriate values. Mistakes in protection can have catastrophic consequences, while getting it right ensures that, in a worst-case scenario, the fuse will respond and prevent greater damage. Ultimately, a small, inexpensive fuse can mean the difference between a manageable incident and a costly breakdown—or even a tragedy—making its correct use a pillar of electrical safety.